This is a continuation from Part 1, reporting on five nights in the Eastern Sierra region of California. For more on the region and such, see Part 1.

I woke up fairly early next day, not getting enough sleep for some reason. I tried to just relax for a while and fall back into sleep and succeded partially. Anyway, I did feel sufficiently rested to start my day.

Camping always comes with chores, like organizing stuff in the small space one has, cooking and cleaning, and also taking care of yourself. It was warm, but breezy enough to not feel the heat as much. I made myself coffee and rehydrated some dehydrated soup. To spend the time during the day, I worked on planning and making measurements for some telescope / camping setup improvement projects. There was enough to do. I also worked a bit on pruning my observing list. I also tried iPhone’s satellite messaging feature to contact my family and friends – it works but it’s nowhere as reliable as my Garmin InReach in keeping connected to the satellites. Somehow just the project planning and chores made the few hours of daylight feel short and the light was starting to fade before I knew it.

I was excited to start my observing early, with no set up work whatsoever! I pulled the covers on the telescope and started collimating it. In the excitement of collimation, I decided to try improve the secondary mirror angle. Oops I messed it up badly! I vaguely recall tinkering with it in the first place because I noticed some minor issue. Yes, my secondary mirror wasn’t exactly positioned correctly, but I just made it worse without having the right tools to fix it.

The sight tube I purchased from Agena Astro was too long, and my janky home-made collimation cap to which I had taped in a 1.25-inch T-ring adapter to act as a sight tube was inadequate. The positioning of the secondary mirror can impact how much of the telescope primary mirror’s aperture is actually used, and a regular laser collimator will not help with this step. Looking at the defocused star image, and also sending my mobile phone flashlight through the peephole in my collimation cap, it was clear I was maybe getting about 25 inches of aperture and not more. I was disappointed, but I told myself I’d spend time and fix this somehow with some thinking.

Normally this operation has to be done in twilight, when you can see all the reflections properly, and it had already gotten too dark to fix this. I used my cellphone flashlight to illuminate the secondary mirror from below so I could see its outline. Eventually I realized that I could put my Glatter parallizer (1.25” to 2” adapter) on the inside end of the focuser drawtube and the janky collimation cap on the front end and make an “adjustable length” sight tube, by moving the adapter in and out! What a find. With this, I quickly managed to adjust the secondary mirror’s position. Not only was the angle off, somehow the axial distance was also incorrect, and this helped me tune it. It usually takes two people to tighten the mirror in place, one person looking through the peephole and holding the mirror in place, while the other operates the wrench on the lock nut. I somehow managed to do it by myself. It wasn’t perfect, but I had gotten to where I was at most losing half an inch of aperture! That was good enough for me to proceed with observing. The ultimate test for me was to see if the (substantially) defocused star image appeared circular, indicating that all of the mirror was being seen, and it was finally close enough. I started observing at about 21:20 PDT, which meant I’d lost perhaps an hour and a half of observing time to this problem.

To relax from all the tension around the secondary mirror, I pointed to the bright globular cluster M 30. It sports two chains of stars that look like legs, which gives it a nickname “walking globular cluster” amongst some of my friends. Then I looked briefly at Saturn with the edge-on rings and moons, and then went to M 22, the big globular cluster in Sagittarius. With that I was ready to start digging into the deep sky.

Galaxies Galore

I started on

was next, also known as SPRC 69. SPRC stands for the Sloan Polar Ring Catalog, a catalog of confirmed, candidate and similar-to polar ring galaxies. I had not expected my 28-inch to reveal the faint polar jet-like structures from it, which I believe is the polar ring viewed edge-on. I got several flashes of the ring at 583×, and the north-northeast filament was easier to see than the other side.

came to be on my list from Steve Gottlieb’s article on objects in Delphinus, published in the September 2025 issue of Sky & Telescope magazine. I thought it was a pretty neat merger, and gave it a look at 583x. It appeared to have a V-shape with a knot hanging off one of the arms of the V.

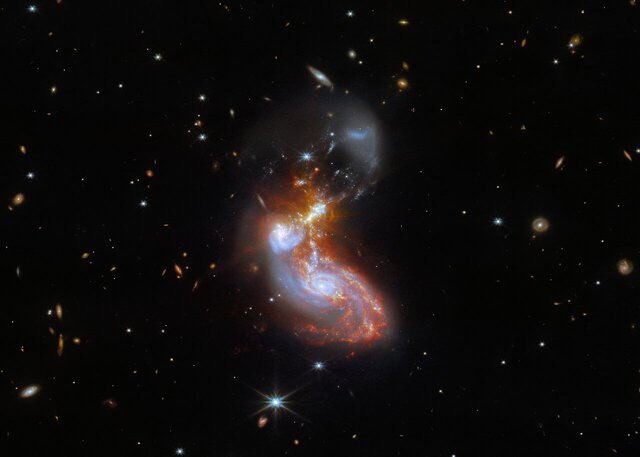

Above is a James Webb Space Telescope image of II Zw 96, click here for more

Above is a James Webb Space Telescope image of II Zw 96, click here for more

Lacerta

Tired of chasing galaxies and not knowing what to observe for a bit, I actually hit some open clusters in Lacerta.

I moved on to the planetary nebula

, called the Lion Nebula, was a field star-hop from Abell 79. I picked it out pretty easily as there was a clear glow running through a star-devoid region. That was in fact the most contrasty portion, a wall of nebulosity running roughly east-west and lying south of a keystone-like asterism. There was patchy nebulosity scattered around mixed in with starglow to the northeast of this filament.

came next, and I hadn’t seen it before. It was dim! I could only confirm the eastern rim of the nebula, and of the western rim I perhaps got 2–3 flashes after knowing where to look.

Maybe a horse but not a flying one

After this observation, I was going around to my truck to get something, and I heard something rustling in the bushes not too far away. I freaked out, tried to quickly get my hands on some pepper spray just in case. I threw some light in the general direction, and the outline of a sizable animal with retroreflective eyes staring at me came into view. My heart racing, I shone a white flashlight at it trying to determine what it was. I’ve never seen a mountain lion at night, but the size certainly seemed compatible. Of course I guess a mountain lion would be prowling and not reveal itself this easily, but I was nervous! The animal showed little fear from my loud noises and walked along its way, getting a bit closer to me in the process, still looking at me. I couldn’t quite see anything apart from its eyes with my cellphone flashlight. I should’ve brought out something brighter, but I was facing the animal and watching it for my own safety. When it got closer, I realized it was probably a burro. There are invasive wild burros in Death Valley. It could’ve also been a particularly large bighorn sheep, as it seemed like it had antlers. In any case, it continued moving on, staring at me while I stared at it. I eventually bent down and picked a few rocks and flung them in its general direction and it scurried away. Phew.

I took a moment to calm myself, and tell the rational thinking which was coming back that the animal, whatever it was, was not a threat and it had scurried off although not too far away. I couldn’t hear it or see its eyes anymore. I texted my friend over satellite about what had happened and calmed myself down. I sat down at my “desk” (my truck’s tailgate), happened to look up and saw a beautiful fireball with a long trail. All was well. The night sky is always a source of security for me.

A flying horse

Next up was

Staying in Pegasus,

More Hickson groups

in Andromeda was bright. I immediately picked up on a mottled, even resolved, galactic glow in my wide-field finder eyepiece. Tacking on 291 I was able to pick out the four members, all visible continuously to averted vision simultaneously. I also picked up

in Cetus, in contrast was surprisingly dim.

Sculptor

I found myself digging down in Sculptor again.

Deep-sky observing is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results. Although the

NGC 147 and NGC 185

These two less well-known satellites of Andromeda Galaxy are found about 7.5° away in Cassiopeia. Of course, I’ve seen them before, what brought me here are the globular clusters. On the Extragalactic Globulars page are listed the brightest globulars in eight galaxies, including

is the brightest of the four clusters. I had struggled to confirm it in my 18-inch, finally getting a convincing observation after a few attempts. In the 28-inch, it was much easier in comparison, of course! I’m not sure why Hodge V is marked as brighter, because

Two globulars in NGC 147,

At this point, it was 4:30 AM, I was tired. I shut down for the night.

Click here for Part 3